Alchemy of the soul

The process of integral psychology

Editor's note

This article continues to explore a soul-centred psychology. This is the case of a woman who could heal her conflicts by going beyond a normal framework.The following four stories illustrate the practice of gaining awareness of the full spectrum of consciousness in the healing process. In these stories, — birth, death, spiritual emergency, transforming trauma and contact with the transpersonal have become vehicles of conscious evolution that cross traditional and developmental boundaries. Each story reveals a personal process which unfolds in a new awareness of creative possibilities — an awareness accessible to all human beings.

These tales of transformation invite the reader into four unique worlds that unveil the interplay between personal and transpersonal realities. In lives that are distinctly different yet remarkably comparable, each individual has experienced a growth of consciousness from contact with personal and transpersonal dimensions. By accessing this integral wholeness, each person in his or her own way has transformed an ob-stacle, explored a higher aspiration and furthered the journey towards liberation. May their stories inspire and serve others on the same road.

Where are my children?

Opening the door, I find myself face to face with Joshua Callahan, newborn, nestled on his mother’s chest. Pushing a stroller, Patrick Callahan flashes a smile. Focusing on Joan’s shining face, my mind traces the torturous route leading to this happy scene.After graduating from college, Joan entered therapy in 1987. Her first utterance, “I don’t know who I am,” told me that her journey was to be one of self-discovery. It took twelve years to realize this truth.

For two years we worked consistently on Joan’s relationship with her parents, and with the men in her life. We confronted her parents’ divorce, living with a depressed mother, a verbally abusive father and her role of ‘mother’ to her younger brother. Sobbing, she repeatedly voiced her lifelong dream: to have a child with a loving husband. I could not discover the root trauma responsible for her extreme longing. As early as age eight, she wrote passionately in her journal about a child she believed she could never have.

In 1989, Joan moved from New York to Sitka, Alaska. On the night of her arrival, she walked into a bar and met John, the man with whom she would spend the next ten years. Instantly, she recognized him. When he left the bar, Joan followed. Unchar-acteristically, she asked, “Are you shy, or are you married?” He said that he had been recently separated from his wife; then revealed that he had not left on his fishing boat that morning because he had ‘sensed’ her arrival. Roughly, he warned her, “If we are to have a relationship, it will be good for me and bad for you. You will have to do all the giving.” Eventually, Joan was to endure the truth of his prophetic prediction.

When they parted that evening, Joan experienced a familiar panic attack. Separation from a loved one had always triggered the feeling that she was going to disappear. Though she had just met John, she suffered the familiar numb tingling in her hands, and wept hysterically. At last he assented, and she moved into his house — initiating a relationship filled with pain and frustration. Though she took care of John’s two children, his ex-wife made all the decisions. Her sense of enslavement and John’s depressed, passive-aggressive behavior imprisoned her in a state of constant despair.

I worked with Joan eight years, primarily via phone and letters. During her rare visits to New York, our work centered on her relationship. Yet always, in the end, she could not leave John. “Somehow, I have to make it right with him,” she sobbed.

In August of 1997, Joan’s ninth year with John, I received a letter from her, “Living with John is killing me. But I cannot leave.” Desperate, she asked to visit me for prolonged intensive therapy. She needed to know what strange attachment kept her tied to John. Though overwhelmed by grief, she was keenly aware of the deep schism in her life — strength and self-direction in her work (as therapist, teacher and artist), yet utter helplessness in her relationship.

At the end of August, 1997, Joan arrived for our first three-day intensive, her leg infected, her feet covered with rashes, fungus and eczema. Once again, with a sense of powerlessness, she informed me that she could not leave John. Employing a series of Gestalt exercises (in which role- play evokes different parts of the personality), Joan contacted a part of herself which she identified as the ‘cowboy’. Though this inner figure gave her more freedom of expression, I sensed it would not solve her dilemma. I decided to use holotropic breathwork. Created by Stanislav Grof, breathwork employs deep, rapid breathing. Utilizing music/sound played at extremely high volume, an altered state of consciousness is induced. Memory of one’s personal/psychological history, of the time in the womb, even of the birth process itself may emerge, as well as mystical, shamanic, past-life or near-death experiences. The following sessions revealed two separate past-life stories, containing characters Joan had never met, in settings far removed. Leading her far beyond her conditioned reality, holotropic breathwork allowed Joan to glimpse, for the first time, the source of her suffering.

After five minutes of deep breathing, she shouted in a strong African accent, “Where are my children?” Two hours of perpetual movement (involving arms, legs, pelvis, shoulders, head) accompanied by an overwhelming anger, grief and terror. Awestruck, I witnessed the transformation of a white woman from a sophisticated New York into a black woman from a primitive village in Africa. Shrieking with agony, reliving the loss of her children, she stood up, ‘beat’ a drum, tore at her hair, begged to die and berated herself for being a bad mother. Joan was in an unusually deep trance. No one in an ordinary state of consciousness could sustain this intensity of movement and feeling for two hours. Nor could they stand up without coming out of trance! (Except in cases of somnambulism, standing or sitting up will bring the person back to waking consciousness).

At the end of the session, shaken by her own experience, Joan related the following:

“I am a black woman living in a small village in Africa. I see my surroundings clearly and am immediately aware of grief and terror coursing through my body as I search for my three children. Again and again I shout, ‘Where are my children? Did you see my children?’ As I run along the dirt paths, I am aware that a stampede of wild elephants is headed for our village. We must leave or be trampled. My ten-year-old son, my six-year-old son and three-year-old daughter are nowhere to be found and I am faced with a terrible choice — leave without my children or be killed.

Ultimately, I am forced to leave with the other villagers, never having found my children, never knowing if they were alive or dead. Now I am on a dirt road beating my drum, calling , ‘We are leaving, where are you, my children?’ My feet and legs feel hollow since I have been separated from them. I can see my slender body, my long legs and arms, the pale palms of my hands and soles of my feet. I wear a brown fabric wrap and a short necklace of large, amber-colored beads. My hair is closely cropped. I cannot forgive myself for leaving. I should have stayed to be killed with my children. I imagine my eldest son returning to find his mother gone. I would rather he found me dead. ‘Oh! What kind of a mother am I ? ’

For many years, I play out my role in the community, but I am not alive inside. Repeatedly, I cry out to God, ‘I wish I had died instead of my children!’ Standing in front of our hut, I vow that I will find my eldest son. I vow that I will never leave him again. I vow that I will never leave anyone again!

I wait to die and finally see myself dead, floating on the water in a wicker/straw casket. I am lying on my back and see my hands with their long, thin fingers folded across my chest. Suddenly, I see a (white) brightness above me and I slip out of my body. I look down at myself floating on the water and repeat over and over, ‘I will never forget my children. I will never leave anyone again.’ My eldest boy’s face appears. I tell him how much I love him; that I will never leave him again.

Near the end of the session, as I open my arms to embrace him, I suddenly feel the spirit of my child-to-be and realize that there is no room for him in my present life. A profound ‘No’ arises from within. I cannot betray my first son again. If I let this new child in, I will lose my boy. I am very confused.

I experience great compassion for the African woman (who is I). But since she/I has not forgiven herself, what can I do in order to have a child in this life?”

On the third and final day of our work, Joan and I gathered together emerging threads of insight. Reminding her of her present dilemma (of living with a man who did not want any more children) Joan cried, “I am in this relationship not because I want to stay, but because I cannot leave!”

Suddenly, reverting to her fear of having a child, Joan experienced a spontaneous vision of her oldest African son. The modality used to help her was process acupressure. As I applied pressure to the acupressure points along the meridians, Joan gained access to an emerging story.

As with the holotropic breathwork, Joan now returned swiftly to her life as an African woman. Once again she relived the crying, pleading and apologizing. This time, however, she not only identified with, but was witness to the African mother’s intense pain. This allowed her to bridge the relationship between the two lives.

Realizing that the African mother’s guilt strongly negated her desire to have a child, Joan experienced the latter’s returning to her home with her three children.

“This is our story,” she tells them.

“There is a white woman in a different lifetime who wants to have a child. This woman can be mother to you.”

The oldest boy, however, resisted. Trapped between two worlds, both Joan and the African woman could no longer evolve.

Despite her desire to bear a child, Joan was terrified of conception.

“I am weak. I’m not as strong as the African mother. I can’t do it.” Calmly, the African woman replied, “You are strong. You will be a good mother. I choose you!” At these words Joan, too, became calm. “You are right!” she cried. “I am strong! Allow me to be mother now! Forgive yourself and set us both free!”

Smiling, her arms wide, she said, “As I let go, I saw the African mother’s transparency enter into me! I had become the major figure.”

Joan left our three-day intensive awed by the depth of her experience: armed with new understanding, she returned to Sitka. Although apprehensive, she revealed everything to her partner.

“I told John about Africa, holotropic breathwork, process acupressure and souls. He listened intently, asked for details. Shedding tears, he reminded me of our uncanny recognition upon meeting. He talked of the white light I had seen; claiming that he also had seen this ‘great white light’ as a child. I was flooded with feeling: could it be that he was my eldest African son? Though he could not remember that other life, I begged his forgiveness; I spoke to his soul, not to his personality.”

Joan’s hopes kindled but four months later, old patterns surfacing, she returned. As in our first intensive, she adamantly refused to leave John.

“I owe him. I am responsible for him.”

It was during this session that she spoke of her first love, Patrick Callahan (whom she had met at age seventeen).

“No one ever loved me so deeply.”

When she left for college, Patrick gallantly told her that he loved her, but she was not to feel guilty if she dated others. A year later, she broke his heart. For seven years, however, they kept in contact.

In September 1997, still in Alaska, Joan had a significant dream. She recognizes Patrick on a bus. Though he is with two children, she senses that he is unmarried. To whom did the children belong? Waking, she notes the time. 3:45 am. Checking her answering machine, she hears Patrick’s voice. “The time in New York,” he says, “is 7:45 am.”

In December 1997, Joan had a second significant dream in which Patrick urges John to end his relationship with Joan: he is the one who can offer her love, marriage and children. Upon waking, Joan again receives a phone call from Patrick, but this time, she returns it. While he tells her that two women are about to give birth to his children, he still reiterates his offer:

“Come back to New York. Marry me. I have a house and garden. We’ll have children together.”

Joan’s therapeutic process continued. Once again she returned to her African lifetime. Speaking in strong dialect, she pleaded with her elder son for forgiveness: as I encour-aged her to let him go, familiar separation symptoms surfaced — panic, pain, intense tingling in her hands, but for the first time, she realized that she was holding him captive.

“You are free!” she cried. “Live your own life now!” As her sobs diminished, her left hand clasped her shirt. I applied pressure to this hand. “Is this where you keep your children?” I asked. Relief pervaded her body. “Now I will have a baby,” she said. “My African children will live in this child.”

Suddenly, she was back on the dirt road in Africa — her legs and feet, however, no longer hollow. “Bright, flashing, white lights circle my head!” she cried. Though she continued to communicate with the African woman, this session liberated her from the trauma of her past lifetime.

The synchronicity of Joan’s dreams and Patrick’s telephone calls at last broke a ten-year pattern of frustration. On the third and final day of our intensive sessions, Joan’s underlying anger surfaced. Recalling her mother’s fragility and her own hostility, she explored similarities between her mother and John, “I can’t trust either of them. I can’t trust anyone!” Lack of trust now became our major theme. During process acupressure, Joan moved from a mental to an imaginal level:

“A blue-green egg covers my womb. It is my shield.” “Can you imagine removing that shield?” “Only for Patrick, He is the only one I trust.”

After leaving, Joan called Patrick to probe his dilemma. While he did not intend to marry either woman, he still felt he must give their children financial/emotional support. Despite this entanglement, Joan knew that she wanted to see him again. She returned to Sitka apprehensive, but determined. Thus began the process of separation. Within a month Joan left John and flew back to Patrick in New York. Now, however, Patrick became ambivalent – resurrecting their relationship meant facing the wounds of the past. The birth of his first child, Justin, led to visitation, child-support, a second job and a hostile mother. Once again Joan was an outsider. The reality of two hostile mothers and their children exacerbated her core issues: she returned for another holotropic session.

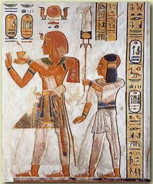

The following is an account of Joan’s second past-life recall. Whether one believes in such recall or regards it as metaphor, its effect on the client is the same. After five minutes of rapid breathing, Joan began to cry desperately. Writhing in agony, she rose to a kneeling position and began to move sensually. Hand and arm movements synchronized with those of hips and pelvis, she displayed an amazing mastery of Middle Eastern dancing. Alternating between dancing and despair, she revealed the following story:

“I was a dancer in the Egyptian royal court. One night I was raped by the king and gave birth to a boy whom I named Niman. Believing I had betrayed him, my husband, Petak, gave the child to the childless queen. Hearing my child’s cries for me, when he was six, I plunged a knife into my heart. I died blaming myself for separation from my son.”

Joan instantly grasped the connection between her Egyptian and present life. The dancer was hated by the jealous queen; Joan was hated by two jealous women. The king’s first child was favored by his father; Patrick’s first son was favored by his father. After several months, she returned for a third holotropic session, re-entering her role as a royal dancer. She became keenly aware of her confusion about mothering children who are not her own and her feelings of inadequacy about being a mother. As a result of this journey Joan’s heightened awareness helped her to control herself. She returned in early November, 1999, for her last holotropic experience before conceiving. Here is her account:

“I began my last session with continuing memories of children lost. Flashes of light were accompanied by the familiar torture in my chest. Experiencing the pang of losing child after child (in different lifetimes), I actually saw their faces! I called out their names. When the African woman appeared, I begged her for help. Intuitively, I knew that the Egyptian woman would sabotage me. Once again, I relived the Egyptian lifetime. I experienced myself as Joan, lowering the Egyptian woman into a coffin. I said goodbye. Now the African woman became my guide. ‘Trust and love your husband,’ she said, ‘Take care of your feet.’ When I lost my African children, I lost all feeling in my feet and legs. In this lifetime, they have been covered with eczema, psoriasis and fungus — which cleared up after I left John. Opening my eyes, I knew for the first time that I would have children.”

Joan went home, armored by self-belief. A few weeks later on December 15, 1999, she discovered that she was pregnant! Her story is a truly astonishing example of the power of transpersonal psychotherapy. A purely personal approach could not have accessed vital information from past births. Let me state again — for healing to occur, a philosophical/spiritual belief in reincarnation is not necessary (on behalf of either the therapist or the client). Whether viewed as stories from the unconscious, or as past-lives, the effect is the same.

In each story, Joan recognizes a character with whom she identifies. She also recognizes other characters as people in her present life. Although psychologists like Roberto Assagioli theorize about sub-personalities, Western psychology speaks of each individual as having one personality. Deviations are seen as pathological manifestations (of an alternate personality) or dissociation from the sense of self. In Joan’s case, healing demanded the accessing of various personalities and relationships (from different lifetimes). Carrying the personality of the African woman, she unconsciously created an obstacle to childbirth. When she entered into a relationship with her, she removed the obstacle. A psychology honoring the soul as the center of the being reveals both the African woman and the Egyptian dancer as vehicles manifesting the one soul.

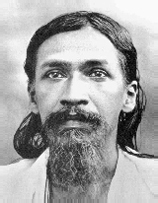

“Man is in his self a unique Person, but he is also in his manifestation of self a multi-person; he will never succeed in being master of himself until the Person imposes itself on his multi-personality and governs it..(1).”

From this perspective, Joan’s past-life exploration illustrates the effect of multi-personality manifesting in the service of the One Person.

Postscript

Joan’s work of clearing the transpersonal trauma opened the way for Joshua’s birth. However, his birth set the stage for confronting yet another trauma — the horror of her childhood. As a mother she stepped into a constellation of people and events that replicated her early life — a house in the suburbs, an absent husband, isolation, two angry women and fear of being alone with a baby.Plagued by panic attacks whenever Patrick left the house, Joan returned to therapy. Following the process of the panic, she remembered being left with her depressed mother and younger brother; Joan was five, Eric, three. Her father’s departures set her on a survival course. How could she control both her brother’s and her own behavior so as not to disturb her mother, who beyond periodic trips to the kitchen for vodka refills, spent her days in a darkened bedroom? Any noise sent her into uncontrollable rage.

Joan’s strategies to keep the beast at bay included: playing quietly with Eric in her room, taking him outside, and entertaining him in the family car. Her mothering of Eric paralleled her mothering of Joshua once her husband left for work. In a state of terror, Joan fled with Joshua, driving aimlessly until Patrick returned.

Then, one day, in therapy, Joan contacted the source of her trauma when she remembered playing in the car with her brother. Suddenly, her crazed mother appeared. Regressing to age five, Joan whispered, “Shh, Shh. Eric, get down....hide! No! Mommy, no, no....!” Screaming and flailing, she curled into the fetal position, clutching her throat and gasping for breath.

This was the beginning of accessing several traumas in which Joan had nearly died. Some were perpetrated by her mother; others by a sadistic nanny who attempted to smother and drown her. During these attacks Joan left her body. “I could easily have died,” she said, “but I had to return for my brother’s sake.”

Horrifying and incongruous, Joan’s experiences dramatically highlight the powerful connection between personal and transpersonal healing.

Reference

1. Sri Aurobindo. SABCL,Vol.19.Pondicherry; Sri Aurobindo Ashram, 1970, p. 897.

Arya Maloney is the co-founder of the Mindbody Centre in Kingston, New York and holds three graduate degrees in chemistry, theology and psychology. He has been teaching in colleges and universities.

Share with us (Comments, contributions, opinions)

When reproducing this feature, please credit NAMAH, and give the byline. Please send us cuttings.